From Oscar of Between, Part 32 B Excerpt

by

Betsy Warland

The Greater Victoria Highlands forest. Beth and Oscar have just had a silky swim in the intimate cupped hand of Eagle Lake. Beth’s telling Oscar about her new writing project, “invented histories.” She’s questing for the way obfuscated memories are housed in bone marrow and cells from the beginning of her life, for this is her only option. She hasn’t even a birth certificate. Beth’s brought a copy of one of the poems for Oscar to read. It has a quiet, oracular feel that magnetizes Oscar. Beth comments on how these poems seem to bewilder other poet friends.

“I can relate to that!” Oscar replies.

“Oh, yes!” Beth responds.

“You mean to your new work?”

“No: your work.”

This is so rarely acknowledged, Oscar checks.

“You’ve noticed that?”

“Totally.”

“I’m most aware of it in a group reading. It often feels like I am coming from such a different place than other writers.”

“You are.”

He was born December 23, 1918, in Ft. Dodge, Iowa.

Oscar was born December 27, 1946, in Ft. Dodge, Iowa.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, he enlisted and was stationed on a Navy supply ship for fourteen months. Utterly bored, he repeatedly requested a transfer to a destroyer but his commander repeatedly denied his request. To counter numbing monotony, he began writing vignettes about the small dramas being played out on ship.

Photo credit: US National Archives

Discharged in December 1945, he returned to New York where he’d worked as an editor at Reader’s Digest. Began writing Mr. Roberts. It sold over a million copies: he became “the toast of the New York literary scene.” The 1948 stage version, starring Henry Fonda, “was a smash” success.

He died in his bathtub a year later.

Ross & Tom, Published September 21st 2000 by Da Capo Press

His name was Thomas Heggen. He was an excised relative. Here, Oscar thinks of her mother’s plan to take a razor blade and cut out twenty pages of Oscar’s first book. How, subsequently, she never mentioned the existence of her other books to her parents.

Oscar knew nothing of Thomas Heggen.

Then, her brother Steven discovered a new book, Ross and Tom: Two American Tragedies. It was an account of two first-book-hit authors living in New York who soared. Stalled. Committed. Suicide.

Photo credit: Rahat Kurd

Guest Writer:

Rahat Kurd

Vancouver, BC

Rahat at Talon Books

from a work in progress by Rahat Kurd

Who will record, who will accept, who will carry

our acts of inscription?

Some of us are placed in the world

at awkward angles to states of being

others may serenely take for granted –

left agape, unable to imagine

speaking all one language in a family,

worshipping together in the same rituals.

In my family, each one of us is gripped

in the dissonance of the other’s awareness.

If I could possibly relate to you,

who on earth would I be?

To relate is to follow

the outlines of someone’s life

until the moment they become legible,

to discern the entry point and seize it

and say here’s my chance, here I am.

When you read a book containing

no entry point, no sign of your existence,

you must write yourself in.

The danger is that the book

will make you so estranged from yourself

that you will not be able

to compose the courage to grip the pen.

There were no books: when my parents moved

to Hamilton, a few years apart

in the nineteen-sixties,

each of them, from different cities

behind different borders

relating to each other or failing,

across partitions and prejudice,

at awkward angles. There were no books

when I was born, that spoke

of Muslims, or Urdu, or Punjabi,

or the drawing or erasure of borders,

or of even earlier migrations from even further mountains,

of someone having once come

from other people with other languages —

Here is what I decided to do:

Write myself in. Christianity was

everywhere, unavoidable

as churches on every corner,

emphatically not mine,

but the birth of Jesus,

echoed in the Quran,

was a door left open

for the Muslim girl to walk through,

to inveigle herself

between the tinsel angel

and the hunger of the little matchstick girl.

Writing ourselves in

as outlaw, like the alif of the Sufi

on the wall that crumbled under the single mark —

more thrilling than any received narrative,

bound in green, stamped in gold.

I’ll tell you how it was in my family

so you may consider your own

angles of strangeness; how attentively,

with what tenacity

you love and hate.

The day after he landed in Toronto from Karachi,

my father took a job in Hamilton,

at the Dominion Glass Company.

Two blocks away from the factory,

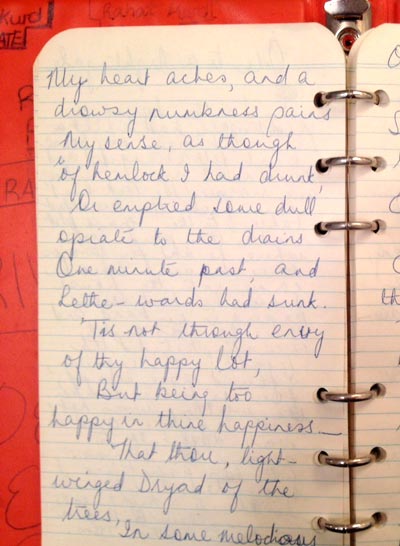

in idle hours in our house on Lloyd Street,

I leafed through the Employee Manual, a small volume

sealed in bright orange and purple vinyl,

inside, six metal rings

clasped a sheaf

of funny little six-holed blue-lined pages

that were a pleasure to turn by hand —

Photo credit: Rahat Kurd

I turned them often, reading

not the rules of glassmaking, not the safety protocols,

but English poems:

Shakespeare, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Keats,

some typewritten, some in my mother’s elegant,

forward-slanting hand; one poem

in her younger sister’s

smaller, rounder, upright letters: Milton’s

“On His Having Arrived at the Age of Twenty-Three”;

clear evidence of how each newcomer

strove to keep poetry in her life

in fugitive pages,

so between Quran lessons

and Pink Panther cartoons

my thoughts could vaguely wander

to daffodils and caves of ice;

to a man who sat under a plum tree for hours.

I ignored or forgot it for months at a time,

then at fifteen made the notebook my own:

lists of songs, funny things overheard on holidays,

letters to write and await in the mail,

in sharp slashes of boastful green ink —

I carried it for a summer, then cast it aside.

After the Dominion Glass Company

shut its gates, after my mother left Hamilton,

the Employee Manual came into my hands again —

My sister Rabia

had written her name

over mine on the orange vinyl

in blue pen, ten years later,

asserting ownership, warning, PRIVATE,

PRIVATE. Inside the back cover,

the faded drawing of a sulky little face

in a party hat; somewhere near the back,

the middle-school confession,

“I hate Micheal Barneby.”

I laughed and laughed:

once, in the same handwriting,

she had left a note on my fridge

claiming Grace Stepney had called.

I think of the ring-bound pages

both transforming the writer

and being transformed

every time it passed into new hands.

I keep the book as record

of the raw power

of the act of inscription,

sparking the me too, me too

desire to emulate

the mere gesture, and more than the gesture —

the will to survive —

to take possession with a pen

of each successive wave

of strangeness that threatened,

but never overwhelmed us.

Untitled Sketch by Rahat Kurd

Photo credit:

Jennifer Lapierre

Featured Reader:

Jennifer Zilm

Vancouver, BC

Website: jenniferzilm.com

I read Oscar’s Salon because

I read Oscar Salon because the scroll of voices has the sense of an ancient manuscript. One voice, then another voice, and then a comment section that seems like annotations.

Profile

Jennifer Zilm is a 2013 graduate of SFU’s Writer’s Studio where Betsy Warland taught her how to use scissors as a writing implement. She has a background in biblical studies, archives and libraries. She is the author of the chapbooks The Whole and Broken Yellows and October Notebook. Her first full length collection is Waiting Room (2016, BookThug).

My dad’s family history was a mix of fact and imagination. He relied on memory to tie together sounds, conversations, remembered photographs, whisperings between adults. But he couldn’t escape the stories in his genes, the ones that haunted him for generations, the ones kept so hush-hush that you wonder if they even know themselves. In my family, everything is hearsay, a myth, even supernatural. I think he “wrote himself in” to the wildness of his imagination to escape his dark reality.

I remembered this recent article I read: http://lithub.com/hidden-stories-and-historical-half-truths-lies-your-ancestors-told-you/

I love Rahat’s two lines: “Some of us are placed in the world/at awkward angles to states of being”. Most of the time (perhaps all of the time?) it is a kind of ‘placed’ not a chosen. A very pressing reminder of this is the narrowing lack of options for refugees who are placeless. Lindsay’s reflection on the hearsay in her family narrative connects with ‘awkward angles’ and the disparity between eye witnesses who literally see and experience the “same” event differently, even contradictorily. When struggling to write The Bat Had Blue Eyes, I finally realized I could only tell a familial story from my corner; that the Authorized Version (my term) was an illusion. Hearsay. Second hand information is usually considered to be gossip or suspect (second hand = the distrust of the left hand). The refugees. Who we listen to is who we become.