From Oscar of Between, Part 22

by

Betsy Warland

Three years ago (November 2012), when Oscar wrote “Oscar, Part 14,” she left something out.

Happened after Arleen returned home. Oscar had planned to stay on and write for two more days. She’d stayed at Deb’s cottage before: was at home there.

After Arleen left Oscar was oddly fidgety. Couldn’t settle down to write.

Became increasingly anxious.

By mid-afternoon – a sentence inserted itself into her mind:

It was imminent. How imminent Oscar couldn’t tell. What to do? Drive around the island yelling out the window: “Watch out! A woman is going to be murdered”?

No one would take her seriously. Oscar could scarcely take herself seriously. It persisted: it was going to happen. There was nothing she could do to prevent it.

By late afternoon, she sensed it had some connection to Deb’s cottage. That night she slept little. Left the island on the first morning ferry.

A couple of months later, Oscar runs into Deb at a reading.

“Did you have a good time writing at the cottage?”

Deb seems fine so all must be well. “We had a great time! As you know, it’s the perfect place for a writing retreat.”

Hesitation hangs between them – Deb’s face of anticipation waits for Oscar’s next words.

Embarrassed but not wanting to appear ungrateful, Oscar admits she had been afraid that something bad was going to happen and left early.

Something bad had. TemPeSt Gale, a friend of hers, had recently been murdered. Her distraught parents were staying in Deb’s cottage.

The next day Oscar goes on line. “900 residents live a tranquil life on Hornby Island … it is the first time anyone has been killed on this island paradise.”

“Police questioned a person of interest visiting Hornby who had stalked Gale’s father and mother to the point where they had sought shelter at a friend’s house overnight.”

TemPeSt – a vibrant twenty-five year old “beloved musician and entertainer” – had declined to join her parents that night. This was Hornby after all.

Next morning she’s not in her boat. She’s in twenty feet of water.

Facedown.

A year later, Oscar sees Deb and asks what has happened: has a murderer been convicted?

“No, but …” [Oscar deletes something here as she revises this text]

“I knew it was going to happen when I was at your cottage but had absolutely no idea who was going to be killed.”

Deb’s taken aback.

“You knew when you were at the cottage?”

“Yeh. Didn’t I tell you that?”

“No. You just told me about being uneasy and leaving because you thought it had something to do with our place.”

(is not enough)

Photo credit: Frank Lee

Guest Writer:

Anne Stone

Vancouver, BC

Anne Stone’s Web site

Novels by Anne Stone include jacks, Hush and Delible.

You lie in a hotel bathtub. The man sitting on the bathtub’s rim is someone’s father, is someone’s brother, is someone’s husband, is someone else’s stranger too.

Once, you were six years old.

On your birthday, your aunt baked you a cake. You knew it would be a good one as soon you saw Betty Crocker’s face peering up at you from the box. Let’s say that your aunt has spent the morning sorting coins, wrapping each in a small square of saran wrap. In her hand, a knife. She inserts the blade vertically, from above. Anyone can see how delicate each movement is. How each stroke is done with care, a single vertical incision.

Your aunt knows to take great care with knives.

Into each slit, she slides a saran-wrapped coin. Afterwards, she hides the imperfections, covers over the scars in the cake’s surface with thick chocolate icing. But she has left this last step to you: the sprinkling of sugary beads. Your small hands carelessly spray these tiny silver bullets over the cake’s surface.

After the party, after the song, after the candles have all been extinguished, you will bite into a piece of cake and, perhaps, finding the lucky quarter, dislodge your front tooth. It’s been loose a while. Still, as you pull the quarter from your mouth and spit out the bloody tooth, you’ll smile. And in your small round face, that smile will be gap-toothed and perfect. It’s a smile you sometimes aim at strangers, though no one ever gets it quite like your aunt. She always loved that pidgin grin most of all. Always, somehow, when you smile, it is your aunt you see grinning back. Conspiratorially. But at the first suck of breath, your smile will collapse. A rush of cold air straffs the raw nerve. The pain is searing but small. So small, it has a kind of perfection. Though you can’t explain it now, one day it will make sense to you. The air has hit something it shouldn’t: a raw nerve that is as complete and exquisite in its expression as the clitoris. The remembered pain is pink and membranous, spiked with red.

Let’s say that, at six years old, you know where a knife belongs. In your aunt’s careful hands.

But the woman, the one you have become, is leaving you now. Because a seam has been incautiously opened.

When you try to picture what has been done to you, it comes to you, a picture of your skin laid out like the pattern for a child’s dress. Crinkly tan paper pulls away from the fabric, and you see that, underneath, there is something torn. A pain someplace pink and membranous, a pain spiked with red.

This is no half-made dress gone wrong, but a living dissection.

The man, the one with the knife, is someone’s father, is someone’s brother, is someone’s husband, is someone’s friend, though by no means is he yours. He leans over you as you bleed out in the bathtub. He hovers, his hand the knife. This man doesn’t see the crumbs of cake still adhering to the blade, doesn’t imagine the ways in which the past stays with us, so that inside of this woman, there is a six year old girl. Doesn’t guess at what dreams lie within the skin.

As time ticks down, it is your aunt that you dream of. She is somewhere, downstairs. You hear her now, drawing a dozen coins from her apron. Mostly they’ll be pennies. A few nickels and dimes. All of her shiny coins, forever inside you now. And when the skin heals over, when you are intact once more, when your surface is smoothed into place, you’ll only be a little bit inside out. It will be such a relief, you won’t even care if the sheared seams show.

It is cold, cold and wet, lying here in an empty metal frame.

If you open your eyes, though, you will be gone from this place, inside of the quilt your aunt has brought you, the one that is as blue as springtime sky. If you open your eyes you will see the care she has taken with each stitch. Any good eye can see the care she has taken, no need to turn a woman inside out to see.

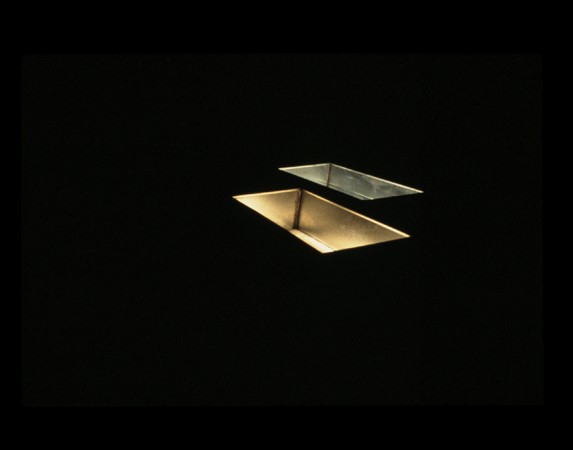

Photo credit: Amanda Marchand

Bodies of Water installation by Amanda Marchand, San Francisco 2001

Photo credit: Patrick Powdermaker

Featured Reader:

Tanya Lewis

Toronto, Ontario

I read Oscar’s Salon because

Reading Oscar is always a different experience; sometimes fragmented, occasionally too hard. Often it is breath catching with an image or a phrase or an insight that drops me beneath the busyness of my daily life. Oscar stops me and reconnects me to what I might otherwise forget.

Profile

Tanya Lewis lives in Toronto and is the author of Living Beside: Performing ‘Normal’ After Incest Memories Return. Tanya enjoys writing and is sometimes impatient with the her long slow scribbling process. Her current project is about grief, loss, memory and accompaniment of loved ones through cancer.

…“– the body as evidence –/(is not enough)…” I really appreciated Oscar’s and Anne’s writings in this salon. It takes a dead woman’s body to get a public reaction, response to women’s chronic lack of safety/chronic vigilance, fear, foreboding in patriarchal society. Since around the world (including in Canada) on any given day there are many, many girls and women being seriously harmed, it is not an exaggeration to refer an international crisis…but this is a crisis that receives so little public attention… I would like to share a poem on this topic:

downed girl

downed 16-year-old girl

corner of broadway and cambie

concussion

confusion, loss of memory

headache, nausea, dizziness

rapid pulse, depression, anxiety

ran away from home

hate messages on her cell phone

from violent father

who gave her the concussion

struck her mother

too injured to attend high school

too young to qualify for welfare money

too afraid of youth shelters

of authoritative adults

too poor to afford rent

too unwell to look for work

or keep any work found

on the ground in front of her

a container for donations

i call the red cross for help

but they say canada

is in a state of peace

and there is no war

It is true that the body as evidence is not enough. Many remain unseen. The jury in the Cindy Gladue murder trial determined that because she was a sex worker, she had consented to the “rough sex” that resulted in her death. Bradley Barton was not guilty, and even escaped a manslaughter charge. In the trial, her pelvis was used as evidence to show how she bled to death from an 11 centimetre stab wound. It was the first time a body part has been provided as evidence in the Canadian judicial system. Her preserved vagina. A dehumanized body of evidence.

I heard about that trial verdict. There were protests resulting from the awful verdict. I feel so strongly about the missing indigenous women in Canada. It is such a national tragedy that Canada is missing justice on. I feel if these women were from more prominent postal codes, there would be huge outpouring of justice. One woman goes missing from another area and background and something is done. A First Nation’s member goes missing, who may also be a sex worker and it is not treated in the same light. We are all equal spirits…despite our differences.

Another compelling, intense Salon.

After reading Temple’s story, hearing her song, I am left rather speechless. I don’t know what to say or think, and I don’t know how much I want to say or think about it, because the more I do, the less I understand. Why do we do these things to each other? Awful things happen. So I’m glad I came here and heard TemPest Gale’s song, stronger than the awful things that happen, sung with what I see as conviction, abandon and wild courage.

I took a lot from Anne Stone’s powerful, visceral piece. I especially loved her line, “Any good eye can see the care she has taken, no need to turn a woman inside out to see.” It made me think of the embodied experience of being a woman and the violence inherent in the various attempts to “know” women, to control women, attempts to figuratively and, as we see, literally, turn the female body inside out in an attempt to gain something like knowledge . . . control . . . power . . . I was recently instructed, “Growing hearts is equally as important as growing minds.” We seem to suffer from a general separation and privileging of intellect and compassion, emphasizing the former at the expense of the latter. The Aunt figure in Stone’s piece is in possession of both. Her careful hands are capable of precise and delicate motions. Any good eye can see. And what’s a good eye? I think just one that looks, appreciates, admires, without needing to grasp, pull, undo, understand.

Here is the space between democracy and anarchy that defines reality rather than overt acceptance of ‘normal ‘ life. I have never, in any of my iterations witnessed the dream-life of normal. The normal-dream is cocoon glue to prop up a bizarre world where even the enfranchised destroy their anima.

VGH emergency nurse of the late 60’s, I relinquished the concept of trust in social justice and joined the army of underground workers who self identified with the people needing help rather than with the helpers. Experience since the 60’s has not changed that ethic and is a slow haemorrhage of my will to be human. The missing women, children and people are under counted. Nature is undervalued and I spend my post menopausal time trying to be post haemorrhagic and present in nature without guilt.

Returned to Oscar’s Salon after a long time.

Oscar’s premonitions, Cassandra like, unable to stop the violence to come. What is this space of knowing, of bearing witness without being able to stop the horror from happening? Auden said poetry makes nothing happen (revising an earlier, more youthful belief in words). The video with TemPest’s raw and urgent singing, was both beautiful and deeply upsetting, knowing, as we watch, what happens to her hope, her fierce calling.

Reading Anne Stone’s deliberate slowing and slicing through time and body – writing as experienced, in the body. Amazed, stunned. And yes, pleasure in the writing, like that raw nerve so beautifully described.

Lindsay’s illuminating comment on body part as evidence is still reverberating in my mind.

this long howl this salon disturbs. i had a dear friend saille abbott who was beaten up because she was other and wasn’t afraid to hide herself. she created movement for the masses and every monday we moved in silence for an hour at the foot of the steps to the vag on robson. moved for peace. oscar and tempest gale and anne stone move me as do all the heard and unheard co-respondents here. small sparks we are. utter flagrance.

“Cut it out!” was a common admonishment when Oscar grew up. Anne Stone’s double edge of cutting (stopping/creating) reminds me not to separate them from one another.

TemPeSt Gale’s murder unnerved Oscar so much that she cut it out when she wrote about her Hornby experience in 2009. Three years later, this cut out story insisted itself into Part 22.

As Oscar selected her excerpt for this month, once again she decided to ‘cut it out’ (not include Part 22). This time, Oscar changed her mind. Knew she was being cowardly; knew that her fear was also a way of disappearing TemPeSt. Cut apart, harm continues. The 1,200 missing and murdered aboriginal women attest to this.