From Oscar of Between, Part 18C

by

Betsy Warland

It doesn’t end there. It never ends there.

Since Oscar returned home, the dismemberment murder in Montreal. Videoed and posted on the Internet. Reported to the police. The police dismissed it as fake.

We don’t want to believe it. Seldom believe it.

A severed hand mailed to an M.P. in Ottawa.

The torso found in a garbage bag on a Montreal sidewalk.

Week later: the other hand; foot. Mailed to Vancouver elementary schools. Then.

A manhunt.

— at an Internet café —

The “person of interest” is recognized from an internationally circulated photo. Police called. Is …

arrested.

In Berlin.

— Vancouver —

Home from Berlin, Oscar reads that Munch’s “The Scream” sells for $120 million dollars. As the gavel falls, it becomes the most expensive artwork sold at auction.

Montreal.

He was an immigrant student.

Gay.

His severed head ( scream ) still not found.

His parents want to return all his parts back to China. Otherwise, he will not rest peacefully.

The Berlin Secession, 1892.

“… a group of artists removed themselves from the official Association of Berlin Artists … after the association succumbed to pressure from Kaiser Wilhelm to shut down a show featuring Edvard Munch.”

( scream )

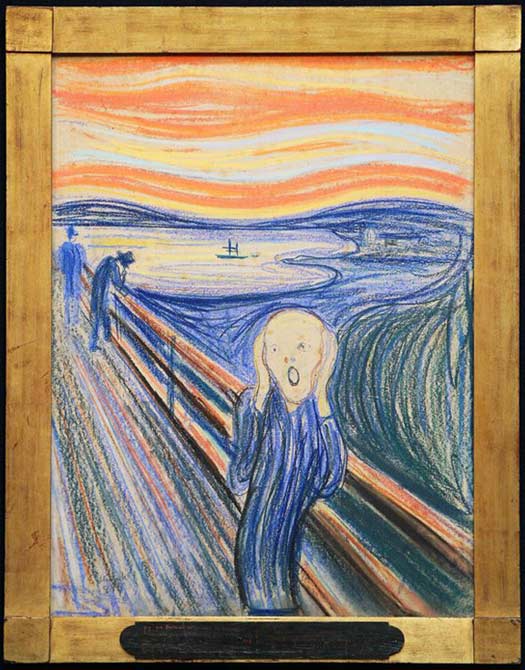

In Munch’s painting a male figure foregrounded on bridge —

shattering sound emitting from his

mouth.

( hands covering ears like parentheses )

June 3, 2012, The New York Times:

“You’re spending $120 million, in part, to show that you can blow $120 million …”

The Scream, Edvard Munch, pastel on cardboard, 1895

The poem by Munch on the frame reads:

I was walking along a path with two friends – the sun

was setting – suddenly the sky turned blood red – I

paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence –

there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-

black fjord and the city.

My friends walked on, and I stood there trembling

with anxiety – and I sensed an infinite scream passing

through nature.

photo credit: Danielle Schaub

Guest Writer:

Denise Chong

Ottawa, ON

a convocation speech I gave this summer

my return to teaching at Sage Hill next summer

my most recent book

Excerpt from The Girl in the Picture: The Story of Kim Phuc,

the Photograph and the Vietnam War,

Penguin Books, 2001. By Denise Chong

The morning of June 9, 1972 unfolded in the village of Trang Bang with an air of resignation. Soldiers opened a detour around the burned-out highway and began clearing the marketplace of debris from buildings that had been damaged by mortar fire. Villagers forced from their houses made their way back, only to find virtually every home had sustained some damage.

Tu and Nu made their way past the scarred temple, its singed and pockmarked walls draped in solidified napalm. The footpath to their house, still wet in places with water that had spilled from severed plants, was littered with tailings of mortars. The bombing had also exposed a network of tunnels dug by the Viet Cong.

The couple saw that their own house, though badly damaged, still stood. Nu had to hold her shawl over her nose, as the closer they came, the stronger was the stench of death that emanated from the landscape of broken masonry and tiles, decimated trees and blasted earth. The couple went only as far as the gate. The only sound was the buzz of flies. Nu noticed the rotting carcasses of her two swans in front of the veranda. She thought of how she would miss their loud shrieks and the way they would nip at approaching strangers.

The couple set out on their mission to find their missing youngest daughter. They joined streams of foot-weary refugees on the highway towards Saigon. Several hours later, they got nowhere at the hospital in the town of Cu Chi. Staff there insisted that they had not admitted a child burned by napalm answering to the description of their daughter, and would not have because their hospital had neither the facilities nor the staff to handle such burn victims. They advised the parents to try Saigon’s largest hospital, the Cho Ray.

By then, day had surrendered to night and to the Viet Cong. Tung and Nu spent the night on a stranger’s veranda in Cu Chi. The next morning, they continued on foot. Several hours later, at Saigon’s Cho Ray Hospital they draw another blank and were told to try the city’s other hospital, First Children’s Hospital. By then, it was dark. The couple slept outdoors a second night, this time on a stone bench. At sunrise, they walked across the city to their third hospital in as many days. They were met with the same denials that their daughter had been admitted. Indeed, it was rare that newly-burned victims of war turned up in Saigon; typically they died before reaching even the nearest hospital.

Before the couple could admit defeat and begin a search of the city’s morgues, they decided to conduct a search of this last hospital themselves. The eight-story building had several wings. Floor by floor, corridor by corridor, room by room, they sorted patients from crowds of relatives bathing them, changing dressings, feeding them. In desperation they lifted cast-aside bedding and looked under piles of shoes outside each room, as if their daughter, untended, might have been pushed aside there. After several hours, they found themselves back on the ground floor.

They sat, exhausted and spent.

Photo credit: Rita Leistner

Featured Reader:

Najwa Ali

Toronto, ON + others

I read Oscar’s Salon because

Oscar asks: “Perhaps memory is not so much ours as we are its. We being merely a vehicle for it. / Its worker bees.”

Profile

Writes, despite intimate negotiations with silence. Crosses borders, sometimes inadvertently. Recent publications include: 1st prize, Room 37.2, a poem in Room’s forthcoming Translation issue and an essay on grief, honour and post-9/11 life in Wasafiri 77 (UK). Trying (hard) to complete a novel, start another and wrap up a collection of short stories.

In Susan Sontag’s book, Regarding the Pain of Others, she writes: “Harrowing photographs do not inevitably lose their power to shock. But they are not much help if the task is to understand. Narratives can make us understand. Photographs do something else: they haunt us.” The two excerpts in this month’s salon remind me of how we understand through narrative. But when the police dismiss the Montreal murderer’s videos as fakes, I question the power of the photograph to haunt us in an age where all sorts of images are accessible within seconds and a google search. Sontag also describes how eventually captions would be needed to understand the photograph however iconic. I wondered the effects of such desensitization when I recently saw the Kim Phuc photograph transformed into a meme where the young girl was being chased by a giggling Prince Charles.

struck how munch’s scream as image (wrote ‘omage) & kim phuc’s (in different medium) are iconic—homage to our likeness in suffering. haunting is to bring home. perhaps writers and poets such as betsy & denise, najwa & lindsay penetrate our desensitised skins—re-mind us of our humanity & inhumanity.

I’ve been struck by how the texts, and the two images they invoke, resonate, deepen and question each other. Stray thoughts here- after days of reading, re-reading Oscar/Betsy and Denise’s texts as well as Ingrid and Lindsay’s insightful comments. Both texts re-animate these ‘iconized’ images, historicize them and force them into communion with the bloodied present – one of dismembered bodies, Jun Lin’s horrific death, and, as I explored more about Kim Phuc, that of Ali Abbas, the child who lost his arms during the US’s 2003 invasion of Iraq. (Phuc’s foundation supported his hospitalization)

Another thought… The time of Munch’s modernism, the late 1800’s, is also the height of European Colonialism. Munch’s androgynous angst-ridden screaming figure, said by some, to be modelled on an Incan mummy, hands held to its ears (parenthetically), perhaps glimpsed in Paris’s famed exposition which was also a triumphant exhibition of its colonial power.

Details resonate. Walls draped in solidified napalm. Dead swans. Parents searching for their children. The desire to find – what? Amidst such loss. And there, gathering, the ghost of capital- in numbers and dollar signs, in government and police offices, in the dreadful meme that Lindsay described, chasing.

For the past few months my “Oscar of Between” excerpts have been sobering. Disturbing. I’ve wondered if readers of the salon would turn away as it’s hard to read; hard to know what to say. Yet, the excerpt Guest Writer Denise Chong chose, and the thought-provoking comments made by Lindsay, Ingrid and Najwa confirm that looking into the “eyes” of these horrific events is perhaps the only way we can gain the deeper insight we are so in need of. U.S. author Sarah Schulman recently said in an interview in Herizons, “Pretending that a human being does not exist, that their experience doesn’t mater, is the centrepiece of the world’s pain.”

These pieces complement each other beautifully; for me the pairings presented in Oscar’s Salon so often deepen the experience of each separate piece. By describing the feelings that the violence described in these two pieces evoke, the writers give us readers space to consider our own feelings more easily. Good medicine for hard times!

The past few weeks have been very disturbing in terms of how gendered violence is spoken of, silenced, used to particular ends – in Canada. Within this context, Betsy’s and Denise’s writings gesture to a wider world within which violence works. What is a violated body? Whose violated body is seen as worthy of public outrage, and whose body is not? What happens to a body after violence?

Here in Canada- the public outrage about JG/CBC has centred on violence against middle-class, young, ‘educated & employed’ women’s bodies but no such outrage accompanies the Canadian state’s refusal to acknowledge the scandal, the horror, of 1200 disappeared aboriginal women’s bodies. To acknowledge this scandal, one would have to dig deep into the horror, the violence at the heart of Canada’s very existence as white settler colony.

If Vietnam functions as an acknowledged mirror to the USA’s imperial desire, but also as a visibilized and much narrated history, site of US guilt, movies, novels, narcissistic remorse etc, then compare this to all the ‘invisibilized’ US assaults on other nations in the past (Congo, Nicaragua, Grenada, Somalia etc) and the current, relentless wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Pakistan, not to mention the undiscussed proxy wars, military trainings, etc undertaken in Africa, Asia and other places.

This long post is perhaps a release of my own frustration at the tight boundaries around public language in the face of violence. What literature offers (What Betsy and Denise offer) is another way to push open the page, teaching us to breathe, look, listen, observe, feel, draw connections between what is made visible and what is rendered invisible.

Thank you, Najwa, for further contextualizing our national relationship to violence. I think of it as a willed innocence (we couldn’t possibly be…) that’s quietly lethal.

thank you najwa—thank you for re-minding us we need to keep on minding

A timely reading of the pairing while the Berlin wall commemorations and Vimy Ridge 100yrs are in full swing. The Scream heightened by each comment of ‘to save democracy or our freedom.’ I like the space in Betsy’s work – how it paced the time and space line of her reflective narrative juxtaposed to the compact compelling nature of the search in Denise Chong’s frantic running and searching. Like ‘OM’, ‘The Scream ‘ vibrates the universal and we always think humans can learn to connect to the vibration but there must be many who are to remain disconnected.

The graveyard and war postings are oddly comforting as political correctness blands out our fairy tale lives. Part of Munch’s comment is his friends walked on and he was left behind to scream. At least we must keep the awareness that much of the world is screaming with us.