Oscar of Between, Part 14, Excerpt A

by

Betsy Warland

Oscar. Divesting. Again. In 2006 it was 700 books to the Saskatoon Public Library. One year later, it was giving, selling, and donating 60% of her belongings from her rental near Main on 22nd in order to fit into her little apartment. Two years later, it’s the emptying out her self-storage unit on Wall Street. Self-storage.

Photo credit: Outbox

Commonplace term unheard of a few decades ago.

When Oscar’s self-is-no-longer-in-storage, she calls her goddaughter Sophie. Will she give her a hand?

They walk down the long hallways to the erratic clanking of Sophie pushing a dolly – soft groan of fans overhead. The numbering logic for the units is confusing and the only landmarks for identifying which hallways they’ve already been down are rodent traps parked here & there. Their voices are tentative as they try to locate Oscar’s unit amidst the endless ellipsis of doors padlocked against natural light, air, theft. Mausoleum-feel. Everything permeated with dust. (… to dust). Then: there. Oscar unlocks her unit’s door. At the sight of boxes piled head-high she fights the urge to relock it. Walk away.

~ the relativity of meaning ~

How little, or of no meaning her belongings are to anyone other than herself.

Decide. Decide. Oscar admonishes herself: get rid of these things.

Some of it is easy (empty boxes saved “for the next move”). Some not: making the decision to throw away 400 of her own books: Inversions,but mostly of Proper Deafinitions – Oscar possessing far more copies than she ever wanted due to her publisher’s extraordinary large print run and subsequent bankruptcy.

Slicing open the top of each box, Oscar winces at their gleaming expectant covers. She sets aside one box of each book to take back to her apartment and wheels the rest out to the dumpster. Throws them over its five-foot high sides: thud. Thud. Box after box. Oscar reviews her logic: tired of moving them (thud) no market for them (thud), no room in her apartment (thud, thud); can’t afford the storage (thud). She does not change her mind.

A peculiar feeling – destroying books you have authored. Peculiar.

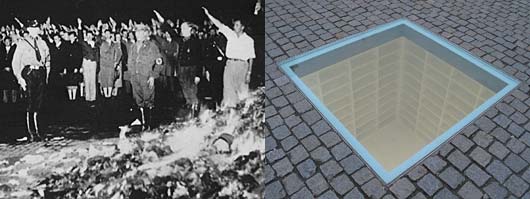

At least it’s by her hand. Oscar thinks of Elizabeth Smart’s irate parents buying up all Canadian copies of By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept in order to burn them. Thinks of the Nazi bonfires of Jewish-authored books. Thinks of Jane Rule’s wine barrels full of her first edition of Desert of the Heart and wonders what happened to them.

Tears. Press. Not so much for her destruction (tho this does appall her) but for the sheer generosity of books – how they give themselves to us to be written then entrust themselves to be held, read, in anyone’s hands.

Guest Writer:

Eufemia Fantetti

Toronto, Ont

eufemiafantetti.com

Excerpt from short story “Loss of Appetite,” published in the collection A Recipe for Disaster & Other Unlikely Tales of Love, Mother Tongue Publishing

Morning dawns warm and pink from the living room; inside the north-facing Vancouver apartment, it’s cold and grey.

He leaves for work. She made him a sandwich of shaved Black Forest ham and cheddar cheese with mayonnaise because he is allergic to dairy and has been trying, unsuccessfully, to lose weight. He will be forced to hate her at lunch, and she reasons that will curb his appetite.

“Today is the day,” she says to the sofa. “Today.” She grabs a suitcase and starts packing clothes. She pulls empty boxes from the closet and ignores labels from a previous move—the one that brought her to this mildewy dwelling—fills each container with random articles of clothing and knickknacks.

At the bookshelf she thinks, too many, they’ll be too heavy to move. She takes down some notebooks and puts them in a paper bag, wishes she could start a fire with them. The apartment is too cold, too grey.

She is tired of being tolerated, of having her taste in books and movies and magazines and everything ridiculed. She can’t remember when the transformation took place—when he went from wanting her to dismissively putting up with her presence—she had been unhappy for weeks before she recognised that the tone of his voice had changed from interested to inattentive. She lost  track of time: the weeks became months, and then, like an old black-and-white movie close-up on a clock with spinning hands, a few years passed. She is too young to feel so unwanted.

track of time: the weeks became months, and then, like an old black-and-white movie close-up on a clock with spinning hands, a few years passed. She is too young to feel so unwanted.

She stops for a cup of tea and sits at the table to rest. The apartment is quiet, a soft buzzing emanates from appliances in the kitchen. The fridge hums while the toaster remains silent. She’s only a distraction so he doesn’t have to be alone.

When he gets home, he notices the gaps on the bookshelf.

“Where are my journals?” He steps around the boxes and suitcases in the hallway as if they had always been there.

“I need them.” She tilts her head toward the bag in the corner

of the living room.

“They don’t belong to you.”

She tosses some scarves into a box and seals it. “Today’s the day, I’m moving to California. It never gets cold there, in Southern California.”

“We can’t go. I have my job. I have responsibilities.”

“There’s nothing to keep me here.”

“There’s me,” he says.

She looks away, stares out the sliding glass door to the balcony. The late afternoon sun streams through the track blinds, patterning pseudo prison stripes on the wall.

I’ve always wondered about . What ARE they? We store ages of our Selves there. OMG Betsy… I am so distressed that all those copies of Proper Deafinitions got dumped somewhere! That was a pivital book for me, and was my introduction to you. OMG. I can’t believe it. Those books are rare and I still covet my copy! I loved who gave it to me, it was like an omen or grace to get given that book, so long ago.

but then I think of the burden of holding and the blessing of becoming Awake to what needs to be let go of, to move forward. Eufemia’s piece a perfect fit and the ideas of walking out of our own prison cages. Thank you for creating this magnificent online Salon.

A very timely moment to read Oscar’s visit to Self Storage. I’m going through my study, making piles of box. The Keep ones. The “to the used bookstore” ones. (There is no to-the-dump pile; but as I work I do skirt a largish box full of one of my own novels… like a box of babies, like a box of all the hopes that went into that book, making little cooing and gurgling noises in there still, so they are safe for a good while yet.

Very apposite combination of your piece and Fanetti’s. Love those prison stripe shadow. And while I’m at it, hats off to Mother Tongue for all the terrific new books coming out.

ps I meant “making piles of books,” of course.

We inhabit a world of symbols; divest them with the power to exaggerate or diminish us. It is painful to dismantle, burn, abandon – for a moment of clarity – before we resume again our blindness. Fear the same lack of meaning; erasure. Stung, cleansed.

Grief: walk straight into loss / splash in its spill and ooze / heft and heave til light.

This is a recurring theme of life and I start to believe it is cumulative to the spirit. This month’s duo resonates with my current writing about imploding due to a lifetime of successfully dealing with losses big and small – some sort of realization that once you’ve discarded it – it’s on the outside and you carry a light version that exerts less internal pressure. The aged may resemble the child in vulnerability – their thin skin of innocence(non-experience) our thin skin of knowledge(experience overload.) The equation: is there enough inner joy to expand and seal off the sucking wound?

I took this month’s excerpts on the road, offered them up to conversations with friends. The significance of leaving someone, but taking their journals with you. In Eufemia’s excerpt, I was feeling only sympathy for the narrator until I discovered the notebooks she was packing weren’t her own! Then I was angry, how dare she? Stealing his thoughts? What a petty move.

Friends who I spoke to about this, some agreed with me, some felt their sympathies grow even greater for a woman who is driven to such measures to take a piece of a man she loves with her. Some didn’t see journals as sacred at all.

We bring our own context to these stories.

When we discussed Oscar’s excerpt, the thought progression was almost always the same. 400 books, tossed away?

Shock.

Anger.

People demanded details, how could this happen, had all avenues really been exhausted for the use of these books?

Mistrust. Assumptions.

Then, their facial expressions adjusted as the knee-jerk reaction subsided, and the image formed in their minds of Oscar (or maybe of themselves) keeping four hundred handheld hardcopies of self in a dark container. Forever.

The effect this might have.

Empathy filled in the context. And it usually does, if we can get past the knee-jerk. Is it a writer’s job to help readers get to that point?

I had the same immediate reaction to Betsy’s purging 400 copies of her book because of how that would feel emotionally, energetically. What writer wouldn’t have that reaction? The reinterpretation of value. Then almost immediately, I thought about it differently. Relief. What a relief. Just chuck them. As someone who has moved a lot and will continue to move, it’s a burden carting books around – even if they’re books written by your own hand (I can only assume that part). Besides, it’s an exercise in non attachment.

People who bought the book and still have it, have the very best possibility that any author could hope for any book they write. Although, based on some of the comments, it’s clear, Besty might have been able to sell more….Good thing she kept one box!

Once an author’s work is out there in the world and some people have coveted it enough to purchase it, I think their job is done.

I think it’s a really good thing. It’s an exercise in Feng shui. You won’t have that negative psychic energy of 400 books that were the result of a mistake by a publisher anywhere in your consciousness or your reality. You’ll only have the act of taking back your power (as you suggest) from a decision to do something about them on your own terms.

***

As for the journals in Eufemia’s story. I didn’t understand why she needed them and I wanted to. Did she need them to keep the pieces of herself that he may have written about in there, that he had, in the end, decided were of no value to him? I really wanted to know why she needed them, not just wanted them.

It happened on January 11th. Just when Oscar thought self-storage was solidly in the past her apartment was flooded after a heavy rainfall. Suddenly home and office were uninhabitable. In the upheaval Oscar finds herself gravitating to water metaphors: wonders how to keep her head above water. “Contents removal”. The detached language of insurance companies. Everything must be packed up: put in storage so the restoration work can be done. I find the ways each of you think and feel your way through the various forms of loss evoked in this Salon provocative; poignant. Perhaps writing is one of our most profound forms of loss.

Wow… the timing of this has me speechless. Just this day I was reading a chapter in Joseph Boyden’s book Orenda, where he shares how a whole village of Indigenous peoples moved regularly. Apparently, they did this every twelve years or so as the land would be depleted so their farming would suffer if they stayed. He describes what they did with their deceased loved ones remains. A twelve day ceremony that brings them right up close to grief and those they love. A leaving of the bones in a way that is heart wrenching.

As authors are our books our bones, the bones of our ancestors? Interestingly enough the title working title of my book is ‘page as bone – ink as blood’. I am really hoping that Talon Books stays with this title but this like many things about our ‘babies’ must be released to those who introduce our babies to the world. Since this is my first book and it is not in print until 2015 I cannot imagine throwing away a box of books that I birthed. So much of ourselves is poured into these creative endeavors that they become extensions of ourselves that stand in for us when those who read them cannot have us in person. I have had Betsy in person and on the page and must say I always look forward to what is next. I trust her and I like to journey with her. That any of this is disposable seems at first glance wrong but then as my more practical side kicks in I say of course. Like the Indigenous peoples in Orenda the land once fertile becomes depleted so it is time to move on. We need to do this from time to time but not without first honouring the bones of our ancestors, those who walked with us ‘here’. Once we do this we can greet the new territory openly and receive the grace it has to offer. So I now find before my book is even printed I am off to new lands, with one eye on ‘page as bone – ink as blood’ and one eye on the future. ~ All my relations ~ Jonina

I was saddened to read about those copies of Proper Deafinitions being dumped, but in my move last summer I, too, dropped off copies of all the books I published at Press Gang to thrift stores, hoping one or two might find a reader. They were like my babies, too.

So sorry to hear about the flood in your place, Betsy,