From Oscar of Between, Part 32 C Excerpt

by

Betsy Warland

Oscar gets the book. Inhales it.

Her facial resemblance to Thomas is startling.

Comprehends her parents’ distrust of books.

Books can kill.

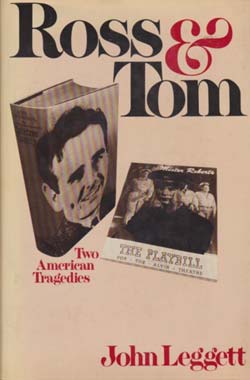

Story of Thomas Heggan by John Leggett

Ross and Tom was published in 1974.

Oscar was married in 1969.

Name of her husband of eight years?

Thomas.

Czeslaw Milosz said a writer in the family is the end of family.

Jamaica Kincaid said she writes about her family as if they were dead.

What do author and family have in common?

A book can bring us to our knees.

It has taken Oscar almost forty years to acknowledge in writing the other author in the family.

After writing this, Oscar prepares lunch. Feels a vast shadow of sadness fall over her.

She accepts the power of the book. This is not what sorrows her.

No. It’s Thomas’ aloneness.

And hers.

Photo credit: Betsy Warland

Guest Writer:

Cynthia Flood

Vancouver, BC

Cynthia at cynthiaflood.com

Oscar’s recent experiences with bees and their beautiful intricate world made me think about what happens when we spend extended time in gardens, on remote islands, or in big parks like Stanley’s. Certainly we breathe richer air, full of more varied molecules. We may feel different — more accurately, allow ourselves to feel different. Larger perhaps? More complex. Not so held by routine. Qualities usually hidden in us can, like yellow catkins held in polished brown casings, push fuzzily up and out. Brain habits, emotional habits shift as we stand still to look. We see more of life and death, witness the catkins’ gold disappear as they transform and reveal leaves. We touch, smell.

These thoughts led me to the camping trips that I, like many city people, take most summers. Not back-packing, no — I mean time spent at provincial campgrounds or forestry sites. Pit toilets, standpipe. We camp at various places for a few days each, one familiar, the others new to us.

Photo credit: Dean Sinnett

People change, and don’t, when setting up house at camp. In our tent, the plaid sleeping-bags lie neatly. Patterns form, a comic simulacrum of home: spoons and mugs arranged so, certain places for his cocoa and my tea. We eye our neighbours, feel their inspection. Avoidance perhaps? Or shared anecdotes of drunk kids recently expelled, of skinny-dipping seniors.

On return from a day’s hiking or exploration, we’re happy to arrive at our familiar tent. A new here.

Here time’s unconstrained by routine. Hours disappear in a silky swim or at the bird sanctuary, till hunger whines and shadows slide over the water and we must cook in the dark. Plans melt. Yes, we’ll take that hike we did last year, then buy cherries, then see the old farm — no, we don’t. We make other things happen. Unexpected pathways lead to snakes or butterflies, feathers and dry bones, and conversations wander to places rarely visited. Secret wishes find voice. Gingerly we become reacquainted.

Yes, campsites make good labs for human behaviour, and I’ve used them in two short stories. “What Can You Do” shows a middle-aged pair repeating a trip happily taken years ago with their then small children. This man and woman, now sad and alienated, argue about their adult son’s addiction till events at the familiar campground force a different understanding upon them. The woman especially must confront her selfishness and fear. (Their story, appearing shortly in The New Quarterly, will be the title of my new book of short fiction, from Biblioasis in 2017.)

An unpublished story, “Rabbit, Birds, Yarrow,” concerns a fiftyish pair in a second marriage. Each has an adult child. At their campground, they witness what they consider bad parenting in young neighbours with little kids. In reaction, they themselves start fighting about their own roles, past and present, as mum or dad. They do try to pull back, to appreciate the beauty of woods and lake, and thus escape their acrimony. Doesn’t work. At both campsites things get worse. What happens to the young family we don’t know, but the couple, burned by their anger, grab the fire-extinguisher of habit. Back inside their dying relationship, they run away.

Death’s also routine on every camping trip I’ve taken, just as at home.

Fox/mouse.

Osprey/fish.

Osprey itself, watched eagerly on a webcam at the ecology centre — but the hunting male, flying home with fish in his beak, gets electrocuted by a faulty hydro line. The female won’t endanger her chicks by leaving the nest; thus, she’s helpless to feed them. One dies. As the other nears death, she abandons the nest.

Car/coyote. Oh so much roadkill, deer, skunk, snake, cat, daily, habitual, the flat bodies taken for granted.

And — a twelve-year-old girl/sudden drop-off at a lake’s edge. She drowned.

We’d camped right there, a familiar there, days earlier, and watched a sunset whose beauty I hope never to forget. This news came on the radio, as we drove home to the city. Silence. We stopped the car. For some minutes. Then moved on towards our usual and continuing life.

Photo credit: Meharoona Ghani

Featured Reader:

Meharoona Ghani

Vancouver, BC

Meharoona on FaceBook

Meharoona on LinkedIn

I read Oscar’s Salon because

Oscar of Between – an immediate pull – in a relationship – a resonation with the times I have tossed – labels – yes – those ones – imposed by others – yes – even those ones – self-imposed. (I still struggle). Oscar of Between – I recall the choice to live in the space of in-between while your words and the words of Mina Shum float from the periphery – “even the margins are a space”. (Was it choice or Divine intervention?). Spaces – I have occupied – as a person of colour – a woman – a person with a disability (MS). (Released. Reclaimed.). I see you – Oscar of Between – in fluidity – like my body – relapse – remitting – relapse – remitting – the body – a “metaphor for distance and identity…This between zone”… – sometimes wobbly and sometimes not – neither in one space or the next – the space of in-between – Oscar of Between – my balancing beam. (Live. Alive).

Profile

MEHAROONA GHANI a poet born and raised in Golden, BC with an MA in Gender and International Development, now living in Vancouver. Once the former director of multiculturalism and anti-racism programs in the BC Provincial Government, now a Community Engagement and Diversity Specialist, Spoken Word Facilitator and Educator with M. Ghani Consulting. A graduate of Simon Fraser University’s Writer’s Studio (2013) and the Vancouver Manuscript Intensive (2014), Meharoona has studied under mentors Betsy Warland and Jen Currin. Meharoona has been featured in six anthologies and has won competitions with the Surrey International Writers’ Conference and the Poetry Institute of Canada. Meharoona is working on her book: Letters to Rumi in which she re-claims, re-occupies the space in-between, the marginalized and hybrid identities, the hyphen in Canadian-South Asian. Select excerpts of Letters to Rumi will be in a forthcoming anthology by Mawenzi House Publishers, Ltd.

Writing in the family is a topic that seems particularly resonant to me as I was the writer in my family. I think I was always a writer, even before I picked up the pen, carefully noting and observing events and material for future stories and poems. This witnessing was always dangerous because my dad was a musician where everything was impulsive but forgettable. Perhaps, I was particularly dangerous to him. I told him once that I was writing about him and he said, I don’t care what you write about me but there are other people involved. I suppose my father understood how a book can bring you to your knees. When he died, I re-read all my writing on him and realized it was like he was already dead, like Jamaica Kincaid said. Is this the required distance that writers put between themselves and the subjects they write about on the page? I felt guilty about it.

Those times when unexpected, life-altering events stop us in our tracks. Words topple. Time morphs. Feelings find their force. Then. Gradually, words take hold; narrative begins to hold us in it arms once again.

how things surface – the gift of in between spaces – campgrounds, familiar and unfamiliar highways – and how we hold what shows up – bees, sunsets, death of birds, the past – much appreciated.

thank you Betsy and Cynthia