Excerpt from Oscar of Between, Part 10

by

Betsy Warland

Oscar sipping morning green tea. Crow catches corner of Oscar’s eye with a sidelong glance as it sidles atop neighbour’s fence in nonchalant nervousness; flies few feet to hydrangea (sidelong glance again). Oscar notices something in its beak which crow deftly inserts into snow; plucks hydrangea leaf from above; taps leaf down on its prize; final glance, then lifts off. Moments later another crow lands on fence above hydrangea. Struts. Assesses. Appears to pick up the scent of prized morsel. Swoops down to ground around hydrangea as first crow returns to fence feigning naivety. Disinterest. The other walking that rocking crow walk does not spot it. Turns. Calls back to the first as it flies away.

The other follows. For, there is later.

Camouflage has clinched its plan.

A few mornings prior, Oscar hears CBC’s Tom Allen’s account of recent study in which a young baboon was chased by its irate mother for some wrongdoing. As the mother baboon nears her young offender, it unexpectedly halts, points accusingly at another. Screams in alarm. All eyes divert as the young trickster handily escapes.

The researcher’s conclusion?

The greater our intelligence, the more we deceive.

Our perfection of lying possibly our paramount achievement.

Concealment. Or camouflage.

(to?) lie in waiting (for?)

Lie (always) in waiting.

Oscar’s 2006 unfinished essay, “Narrative and The Lie”:

“There is never ‘a’ lie but immediately a second lie – the one we tell ourselves that we’ve not told a lie.”

Excerpt from Oscar of Between, Part 11

2009. For over a year now in her new apartment – Oscar awakened by sounds of explosions overhead. Gunfire. Off & on. Day & night. Penetrated by. Sometimes she puts in earplugs (as she has just now). Sometimes, she puts on a CD to camouflage the violent sounds. And sometimes, she puts her fists to the ceiling. Pounds until the old logger turns down his television.

Oscar unnerved.

The more vicious the violence the more we want it. In our homes.

To help us wile away the hours.

Relax.

Before.

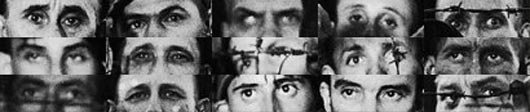

Oscar. Nine years old – riffling through old LIFE magazines – sees photos of Bergen-Belsen prisoners, the first concentration camp to be liberated by the Allied Forces.

These photos her first exposure to unbridled violence

– survivors///////eyes –

look at camera in a way Oscar has never seen.

Before.

She can’t take her eyes off their eyes.

Eyes so far beyond expectation of ever being seen

as humans again.

After.

These eyes haunt her.

September 2, 2013. Oscar searches for this photo on the digital archive of LIFE. Discovers vacant eyes behind barbed wire not in the LIFE archive. Extends her search. Finds it. “The Living Dead of Buchenwald” was taken on April 16, 1945, by Margaret Bourke-White.

Before.

April 15, 1945: Bergen-Belsen. George Rodger was the first photographer inside a concentration camp. His photographs, published in LIFE a few weeks later, are “highly influential in showing the reality of the death camps.”

After.

He quit. Caught himself out, how he’d looked for “graphically pleasing compositions of the piles of bodies” amidst the trees, helter-skelter in deep burial trench, throughout the buildings.

Never worked as a war correspondent again.

2012. Oscar is riveted when she reads A Woman in Berlin by Anonymous – yes, “…was a woman” – its unflinching account of the rape of 100,000 women and girls by the Red Army. Not published until 1959. The reactions from Germans confirm Anonymous’s fears: it is almost totally ignored or reviled for its “shameless immorality.” In the 2002 reissued edition, the publisher writes “…German women were not supposed to talk about the reality of rape; and German men preferred not to be seen as impotent onlookers…”

Anonymous writes: “Our German calamity has a bitter taste – of repulsion, sickness, insanity, unlike anything in history. The radio just broadcast another concentration camp report. The most horrific thing is the order and thrift: millions of human beings as fertilizer, mattress stuffing, soft soap, felt mats – “

Before.

Before Hitler’s unbridled mass murder, he asked if any countries wanted to accept German Jews.

Canada’s response?

“None is too many.” (note)

1982. Cornelia and Oscar biking on the Stanley Park Seawall in late summer twilight: sensation of flying. Glint of smelts in narrow nets reeled in by solitary fisherman: impression of catching splits of moon. Oscar and Cornelia glide side-by-side on the curvilinear, darkening path. Then Cornelia begins. To tell Oscar about the U.S. television series “Holocaust,” recently broadcast after strong opposition. Half the German population viewed it. On the heels of each episode, people poured into the streets. For the first time, talked. Openly. About. It. Wept.

– lying low –

(appearances often lie)

Underbelly of Germany’s elder generations finally exposed.

Guest Writer:

Guest Writer:

Oana Avasilichioaei

Montreal, QC

Oana Avasilichioaei at UPenn

Excerpt from the current work-in-progress Limbinal

Bound (excerpt)

Border, you terrify me. Border, you must dictate your own dismantling or we will perish. Purge. Border, are you listening? Are you empire?

The geography keeps shifting into bloom and decay, thus daring to future. Periphery disrupts the dialogue. Floundering, wet lines linger. Fish bend the creek into its undulations, spring curves. Will these trajectories double back, mislead us? We leave unnoticed through a back gate to make a country elsewhere. We pass the perennials and smile softly. What is our spatialized intention?

Grass River, near Fort Yukon, Alaska Photo Credit: Unknown

Our margin is a pinprick. One of us balances. We enter the idea sideways, disjunctive, producing architectures, performing language, inscribing intervals. The city rumbles into a future because it lacks direction. Frequencies jam. Then our distortions wander. How do we chart this aliveness? Of marginal weathers, of limited instruction, passage inserts here.

Perhaps a meridian is what we look for. If you insist that I take sides, you will misplace me. Instead, I take a barrier to the woods and grow confusion, which might be a sign of health though a leader does not think so.

Border, walking along your edges, I realize that what from a distance appears as edge is simply a faded memory. The moment unravels around us, thought-struck. Border, as an idea, you are impossible to margin. Border, are you listening? Are you hungry? Still hoping for empire?

Photo credit: Oana Avasilichioaei

We vacate the bedroom. We are an outskirt in disguise. Serrate sounding. Sink. Tending to a voice is tending to a throat. In thinking of a tender her, contours ripple. On the eve of the departure, hands are already parched, mouth is already empty.

Border are you watching? Your scope tuned to an obscure gesture, your gaze indifferent. While a rippling refrain of shots, tasers, accelerated feet and sleepless hands rages. Border are you enraged? Are you bored? Are you longing for the fiction of enlightenment?

Daytime obstructs our watching, though we remain vigilant. Our watching, itself a dismantling of boundary. Stutter, cough into. Caught. It’s not about being on one side or the other, but about one side being the other. Border are you nervous? Nerves? Nodes? Are you a call to network?

To cross the island of the self to the island of another. Because she shows me how. Border does this incite you? Does your shore lust for another’s shore? When the other encroaches and thus smalls the self. When the other inspires and thus expands the self. Land of transpresence. Awake.

the dead i pass daily searching for life sparks, why the living goes on for those who have opened the door to its freedom. at senior exercise we walk heel toe along the black line forward and back to regain balance – many cannot do it – to me the line is home.

a gym floor with black tape lines – bloomers from some past century – now I don’t belong here either: they resent my reps, my squats, my walk the black line. It relaxes me to be out of competition, worth even disdain to push myself and go home. My spandex and muscle shirt gauche amongst tee shirts and slacks. My body too light, my face too makeup free. I feel the relaxation of not belonging, of being tolerated – the counterfoil, camo wrinkles buy my entrance.

These excerpts gave me gooseflesh, in my climate-controlled-living-room. With a blanket around my shoulders.

Borders and lines between countries and between cultures. Between individuals. Fear and anger explored here again, and misunderstandings.

Oana:

Border are you watching? Your scope tuned to an obscure gesture, your gaze indifferent. While a rippling refrain of shots, tasers, accelerated feet and sleepless hands rages. Border are you enraged? Are you bored? Are you longing for the fiction of enlightenment?

Betsy:

Sometimes she puts in earplugs (as she has just now). Sometimes, she puts on a CD to camouflage the violent sounds. And sometimes, she puts her fists to the ceiling. Pounds until the old logger turns down his television.

Does the very act of separating ourselves from each other incite violence?

Imagine a wetland. Rising from a world of water, small, shining earth mounds. Trees, the occasional scrub of blackberry occupying the hills. Some bits of dry-land have stone hollows leading down into verdant shadow, or nightmare. Others a bench for sleeping, or a camp chair, empty for the moment. Identity is like this.

Mostly there’s the smell of biological liminality. I can smell myself here. That scent means I was once there. We measure these experiences as moments. Call each Time. This time. That time. With a wonderfully circular reasoning, we say here is where this moment begins. That one ends. We do so on the authority of Time, even though for us Time is a construct of the endless senses.

There’s pressure on the skin. Slide of rain round the chin’s curve as we sit. in camp, peering through the trees. Space.

The thousand bird calls called Silence.

Our dimensionality has more than one vector, so why do we get caught by the tyranny of the eye, the one sense on which we can close a lid? Why do we forget the endless ones__the ear, skin, the vestibular?

A red-winged shoots across the water’s web, tree crown to thorn mound. Locked under pinion, carried along, the i can relocate. oak to berry. Water’s boundary isn’t a boundary. If the leap lasts long enough for awareness to surface, name changes accordingly. This is why I am both truly Carol, truly Mary. Truly, others. Simultaneously :: self+other. Do we need a singular name for this composite? Sother?

But of course, my birth certificate says one thing. So Mary+Carol+__ is truly, but it is also a lie.

If the leap doesn’t last long enough? Still sother but unaware that narrative direction just changed. Is this also a lie, or just another noisy silence?

Between the little wetland islands, do the waterways count as borders__and the connecting earth palming the waters do not? And the bird highway?

When crouched low at the edge of one mound’s ribcage of water, using the eye scribes longing as a stone pathway laid__eye level__lashing liquid ripples. And fails. Is this when s_ repudiates _other and the composite feels the angst of alienation? Is it all the eye’s fault for its lording ways, and perceptual insistence on edges-to-things?

Usually unnoticed, bird transits the eye’s crouching desire :: is it worthy of a laugh that red-winged-shit splats the crown of longing?

What highways are there beside the bird’s wing? Smell’s tree swings__Cheeta outpacing Tarzan. The ear’s skipping leaf as it waves across the water’s surface. and the skin with its millions of mouths sensitive to the world’s swirlings?

Is it merely petulance this insistence upon creeping the edge of water’s fishy dangers, looking to walk on water when we know we don’t have a water strider’s feet?

Do we know the consequences of this insistence? Sure. Buchenwald. Monitoring stations at national boundaries. The fence between your place and mine.

There was a long silence before comments were made on this month’s salon postings. For me, it felt like an extended dash saturated with meanings. Many people indicated they would make a comment but did not. Then the comments began. Thank you Marilyn, Carleigh, Carol (and soon to be posted, Andrea). Your observations, riffs and further contextualizations in response to Oana’s and my texts (and accompanying images) are SO welcomed! Your comments and writing urge me on in my pursuit of some of the narratives that language its very self seems to resist. As betweeness is forever re-inscribing; boundaries are forever re-drawn yet there is always the yet-knot to be undone. To quote Oana, “It’s not about being on one side or the other, but about one side being The Other [caps here are mine].” The nature of narrative is dialogic. Oscar’s Salon has made me far more aware of this than my decades of traditional print publishing: I deeply value all of you who are reading Oscar’s Salon; all of you who tell me how engaged you are by it; all of you who generously include us in on your responses.

I feel like a bird that’s landed in the wrong nest.

All the love was lost, broken, betrayed in my family.

I saw that happen.

I saw that happen

The child says: the covenant of my love has been broken

and this is my shadow. (Mozarowski)

James Robinson and Sarah Mills. “Being observant and observed: embodied citizenship training in the Home Guard and Boy Scout Movement, 1907-1945.”

Avoid the enemy gaze while observing.

Camouflage training establishe[s] a culture of continuous observation of self as well as the enemy other.

Oscar learns from crows. She doesn’t ask for this knowledge. She doesn’t go looking:

“Crow catches corner of Oscar’s eye.”

Oscar exhumes collective guilt. Collective amnesia.

Oscar is “penetrated by” this knowledge. Pierced. Tries to shut it out. “Sometimes she puts in earplugs (as she has just now).”

“The more vicious the violence the more we want it. In our homes.”

This intrusion becomes the portal or “keyhole” into this space of collective amnesia.

“Narrative is the lies we tell ourselves”?

“These eyes haunt her.”

“He quit.”

“Never worked as war correspondent again.”

Scopophobia: fear of being looked.

“Psychoanalysts have linked scopophobia to a repressed fear of looking.” (Wikipedia “Scopophobia”)

Lorraine Sim. “A different war landscape: Lee Miller’s war photography and the ethics of seeing.” Modernist Cultures, 4 (2009).

Miller’s war photography is unconventional in several ways. It does not operate in the service of national myths of heroism or the glory of war, avoids the visual conventions of propagandist war journalism, and with the exception of her images of the camps at Dachau and Buchenwald shortly after their liberation in April 1945, often eschews, or figures in unusual ways, the more violent and horrific spectacles omnipresent during wartime (except in those instances where documenting such scenes was an ethical imperative for her).

It is my contention in this essay that the moral tone and sensibility of Miller’s war photography – both in terms of its content and modes of audience address – are a function of her complex engagement with ideas and the subject matter of the ordinary and everyday.

As critics have observed, Miller’s photographs of seriously beaten SS prison guards at the recently liberated camps of Dachau and Buchenwald also challenge clear-cut ethical judgments and processes of emotional distancing on the part of the viewer. In these disturbing photographs the guards are wearing civilian clothes, kneel before and directly address the camera with frightened eyes, and are heavily framed in small enclosures so as to create disconcertingly immediate and visually oppressive images.

In contrast to other Allied photographers, Miller’s photographs often dramatize the complex relationship between what Dagmar Barnouw describes in her book Germany 1945: Views of War and Violence (1997) as the “great visual clarity” and power of images of Germany after the Allied victory, and the “obscure meaning[s]” and moral ambiguities such images often masked:

After all, nothing was more clearly visible than the devastated, broken German army, cities destroyed and transformed into moonscapes, ghostlike people living in ruins, and the brutalized victims of the concentration camps. But what exactly did it mean, this absolute military and moral defeat of the Germans and victory of the Allies?

Barnouw discusses the central role that Allied photography by both professional magazine journalists, such as Margaret Bourke-White for Life magazine, and Signal Corps photographers assumed in creating a particular public conception of “the German people”. Allied photography, Barnouw argues, sought to affirm notions of collective German guilt. Unsympathetic portrayals of the German military and civilians supported Allied assumptions about the justness of the Allied victory and the retributive behaviours that attended it, such as forcing German civilians, including women and children, to tour the camps and for adults to bury corpses.

Miller, predominantly known to the American public as a fashion and beauty icon of the 1920s and 1930s, is here thoroughly unglamorous and in a very private activity that is not usually made visible to a 1940s magazine public. Her particular physical location in Hitler’s bathtub, associated as it would have been with her recent articles in Vogue about the death camps, would have been deeply disconcerting to Vogue readers. Through sharing with the viewer a banal yet intimate activity, Miller narratively and visually draws them into the discomfiting story of Nazi genocide. Unlike the horrifying, if necessary, photographs of the victims of Nazi violence, images such as this one do not initiate an immediate desire to look away and therefore pass over the underlying meaning or history of the image. It is in this sense that photographs such as “Lee Miller in Hitler’s bathtub” are socially powerful and morally important due to their capacity to make the viewer not just look upon the horrific evidence of Nazi violence, but also reflect on the ideologies that underscored and motivated it.

Archangel Michael beats back the darkness. Wings unfurl. Into infinity.

My arms, broken at my sides. Paralysed.

Loon struggles. Beached. Wounded.

While I stand. And watch.

I am guilty.

Michaelmas. Sept. 29. (Mozarowski)

Death Camps, watching and photography. Still we are unable to use this longitudinal body of thought to stop what we are doing around the world and projecting now into mining expeditions to the moon and beyond.

One brief glance at the personal experience image would seem to be enough to engender pacifism or at least disdain for power.

GUILT is not a motivator, it immobilizes. To engage :: embrace. Embrace life, death and impotency ( note there seems to be no female equivalent to this word.)

While being engaged, a part of me will still watch and experience despair or delight while commenting or questioning why I take this action. The will and action can seem apparent. The consequences are set in motion.

Research into our brains and quantum computing is on the cusp of revealing insights into presence and being that will help us understand the human condition.

ps. These conversations are inspiring. Thnx Oscar.