Excerpt from Oscar of Between, Part 6B

by

Betsy Warland

2008. Fourteen stories high in the Hilton. Looking down on the Detroit River, Windsor Ontario side. Oscar there launching Silences. A book Oscar edited. Thirty-six academics writing on. The river surprisingly beautiful. Changing colours constantly with cloud shadow;

Photo Credit: Unknown

In 1963, at sixteen years of age, Oscar made her first visit here, on the Detroit side of the river. The Luther League Convention. A group from her church taking the train to attend. Detroit. Their anxious mothers. Sew them all matching plaid jackets. Membership flags of their little rural community worn on their torsos. Oscar now gazes across at Cobo Hall: site of their convention. Recalls. Viscerally. Keynote speech by Black anti-racist activist on how ingrained racism is in the English language: “little white lies” contrasted to “a black lie;” “Angel Food Cake” contrasted to “Devil’s Food Cake” A long list. Oscar elated by his intelligence; integrity. His exposure of English’s unacknowledged biases.

Language could encounter silences.

It was then she became a writer.

Two weeks after 9/11.

Windsor, Ontario. A conference on Canadian Modernist Women Poets. Oscar, giving a reading from Only This Blue; a paper on Phyllis Webb’s decision to shift her creative inquiry to painting; stop writing.

Rampant panic. AtmosFear of. A plane’s normal descent of “controlled fall” taken out of control.

To get on a plane suddenly a life & death decision. Then arriving: being that close to it (US under attack).

— the wide Detroit River suddenly a perilously thin line —

Use extreme caution. An impossible imperative. How to recognize a terrorist? And, then what?

Presenters agonizing. Then, canceling.

More attending (majority within driving distance).

The stronger instinct — to gather in the face of it all.

While on the fourteenth floor, Oscar watches a documentary on the Florentine painter Paolo Uccello. Uccello utterly obsessed with three-dimensional perspective, constructed his paintings on a sketched-in underlying “ghost field.” Perspective map for each painting. His “Battle of San Romano” (ca. 1456) to become the organizational template for commissioned British WWI artists; the figurative template for Picasso’s “Guernica” (1937).

By almost 500 years, Uccello’s ghost field foreshadows Cubism.

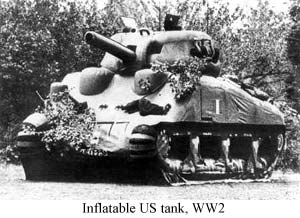

Camouflage waiting in the First World War’s wings.

Second World War: the “Ghost Army.” The US secretly invents a pretend advancing regiment to convince the Nazi’s there are no gaps in the Front Line.

Source: Imperial War Museum (IWM H 42531), UK

Oscar, Excerpt from Part 7

Oscar hunches over writing pad, mind jabbing back fear to write this. This this, that is of little interest to those who insist this this does not exist. The literary seen. For decades Oscar within but not: a knot cinched tight. Her own growing complicity. Recently removing some evidence of this this when preparing her second round of literary archives; speaking less and less about it to her writing friends. Understanding their need to stay on the right side of the right people.

To not stop. Stop. Writing.

Over the years, Oscar has considered it numerous times.

Some of this knot has been Oscar’s doing. Lesbianism and feminism infused her first book. Consequently, Oscar did not come up through the ranks of male tutelage nor male writer romantic liaison.

Some of the knot has been a state of affairs (private and public) far more complex than anyone will acknowledge.

In 1984 (here another Nineteen Eighty-Four springs to mind), Daphne and Oscar cross a taboo line with their books of erotic love poems.

— deep tremors of response —

No two women in English Canada had ever done this before, nor since.

Someone must be blamed.

Now when teaching emerging writers, Oscar cautions: “Be careful. Although many within refer to us as a “tribe,” the literary community is hierarchical: it seldom forgets breaches or forgives. And, occasionally in private, “Although we all cherish the ideal, our art seldom rises above bias and convention.”

On The Drive, Oscar waits to meet a friend for a coffee date at The Continental. Says hello to two writers across the room of the literary knot she wrote about just an hour ago. One is texting; the other reading. She respects them, even senses their own underlying vulnerabilities, yet knows one has caused her professional harm.

Oscar writes this as she waits.

She has not stopped.

Oscar, Excerpt from Part 8

October. Vancouver. 2008. Sunlight through millions of new planes of colour that reflect off colour fallen on ground. To be cupped: held between the palms of these shimmering hues. Oscar rushes outside every moment she can.

The Vancouver International Writers Festival: Hal Wake interviewing Sharon Olds to a sold-out audience. Olds acknowledging her twenty-five-year refusal to agree that her poetry was “merely personal.” Her corrective? Twenty-five years of insisting it was only “apparently personal.”

(all those years = the necessity of)

Then, Olds recounts, after routinely using her disclaimer with a young woman interviewer recently, she noticed something.

Noticed how the young woman’s face collapsed into a silent sadness.

Noticed the toll.

Disarmed. Now secure, she decides. Decides its time to “abandon it” — relinquish her camouflage.

Guest Writer:

Guest Writer:

David Leach

Victoria, BC

www.davidleach.ca

Excerpt from the unpublished essay “Trekking with Americans: Or, how I learned to stop worrying and love our wild neighbours to the south”

“We were two-thirds to the summit, just beyond tree-line, when we saw her shamble out of the mist. Hiking solo, she had the rangy look of a college middle-distance runner. Rain pinged off her cheap plastic poncho and the raw wind exposed the goose flesh of bare white calves. Her eyes had been blown wide, jitterbugged with adrenaline.

“I just came over the top!” she shouted through the air-tunnel roar. “It’s crazy up there!” Then she rushed down the trail and vanished into the fog.

“We should turn back,” Jenny said. It was more than a suggestion.

I wanted to push a bit farther. “I mean, we’ve come this far.”

We scrambled up the incline and spotted two rock pylons that marked the route to the top of Mt. Marcy. The wind tried to lift us out of our boots and then knocked me to my knees instead. How determined was this mountain to howl us off its side?

Somewhere above us, the highest point in New York lay shrouded in cloud and rain. I didn’t want to turn back. I didn’t want to try again tomorrow. It was September 11, 2002, a year since the twin towers of the World Trade Center had fallen. I had decided it must mean something, on this of all days, to stand on the wild rooftop of the Empire State and see who might join us there.

* * *

Our original hankering for a late-summer hiking trip had seemed sensible enough. Just south of Lake Ontario, Adirondack Park encompasses a huge shield-shaped tract of wilderness. We had set our sights on the High Peaks region, near Lake Placid. That we’d be travelling through New York State on the first anniversary of the World Trade Center attacks only struck us later, and so a new plan took shape. I’d heard of other memorials in the park and wondered who might climb 5,344-foot Mt. Marcy, the highest of the High Peaks, on the anniversary. The symbolism seemed inescapable.

Two hours into our trek, we reached the Johns Brook Cabin. We were greeted by Brady, a shorn-haired, thirty-something caretaker in the employ of the Adirondack Mountain Club. We told him about our plans for a 9/11 ascent.

“I’m more of a bog watcher than a peak bagger,” he admitted. “I’d rather sit beside a pond and watch the water striders go by.” Brady had quit a job as a photographer in Manhattan to mind the cabin, study Buddhism and contemplate the universe in a teardrop of bog water. “There’s so much to see in the rest of the park,” he gently scolded us. “But everybody just comes for the High Peaks.”

The region had suffered from its popularity, he explained. Trails had been stomped into thoroughfares. There had been incidents of “lean-to rage”—confrontations over the park’s primitive shelters. Tensions were high, even in this corner of wilderness.

We suddenly felt very un-Zen, two more summit hogs who couldn’t spy the forest for the peaks. We’d come to America, only to trek like Americans.

Brady consoled us with a park warden’s most valuable currency: Stupid Tourist Stories. He told us about the woman who’d gotten tired and ordered her 10-year-old son back down the trail to inform rangers she’d decided to stay the night in a wooden lean-to and would someone please deliver a hot meal and a soft pillow? He described a frantic call that search-and-rescue staff had fielded from hikers who’d demanded an airlift off an exposed peak … because the bugs were too bad.

His favourite, though, was the parable of the broker from the city so proud of his expensive new backpack that, to keep it safe, he strung it in the trees with his food (and his cellphone, wallet and car keys). But the park is home to a sub-set of resourceful black bears—Nyoo-Yawk bears, we-can-make-it-anywhere bears—and that night one shimmied up the tree and disappeared into the bush with the pack … and the cellphone, wallet and car keys.

“That bear is probably still out there,” Brady laughed, “ordering pizzas on his Gold Card!”

when i read Oscar excerpts & David Lynch’s climbing story i’m struck how i/many of us? are caught between being a part of and being apart from. we want to be heard in our society, to have an impact and yet the moment we become part of an organisation, or identify with a tribe, a cause, a country, a belief–what of our integrity? again another conundrum Oscar!

i yearn for transparency but do i dare go without camouflage–do i even know how

makes me think of the Tricycle interview i read online this morning, with Gelek Rinpoche, a lama trained in the Gelugpa tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, who now lives in the US. how he sees the dharma unfolding in the west through individual practice:

Tricycle: …in addition to all the corruption and problems, we think that Tibet did create this extraordinary body of knowledge, and very intense dharma activity was generated by big monasteries, by thousands of lamas. So maybe if you don’t have institutionalization, you don’t have such powerful dharma either.

Gelek Rinpoche: Well, you know what the Tibetans used to say: “The great monastery is like the great ocean. There are a lot of great things and a lot of bad things, too.” What we are experiencing today is not necessarily the product of the great organized institution. Good institutions have a tremendous amount of knowledge to contribute, but what we are really experiencing is the efforts of individual practitioners and the efforts of the Tibetan lamas who have done their practice for thousands of years, lamas who learned in institutions but who practiced individually.

http://www.tricycle.com/interview/lama-all-seasons?page=0,0

The promised riff: concate-

nations/kittycorner.

Oscar, meet Alexander:

@16 & the same river,

same altitude/attitude

not knowing yet about

a thousand gallons a second,

dynamic

time flood of then

to now.

–

Culmination in odd

eddies of circum-

stance

to confess no,

you’re not

alone. Let me

tell you some-

thing, you’re not

the only swimmer

crossing secret

borders straits (de-

troit de-spite water

rank

as sewage,

fish with open

sores, un-

certain depth s/

punctuated

by unfor-

giving

current: it does not stop

–

that book. There,

on the grey carpet

pages spread apart

face down

text holding the moment while

not only one reads:

AlexAndHer

Speak it like this ^

You knew. We knew

if we let go we could

fly

glide

drown . . .

I like how these excerpts blend.

In Betsy’s passage, Oscar is looking down from the 14th floor, across the Detroit River at the US.

In David’s passage, he is in the US looking up towards a summit with some trepidation.

Both are looking for meaning.

People go looking for meaning at the top of things, maybe because it feels easier to finally take a break from endless thought and action when there’s nowhere else to climb? But (and the park warden in David’s excerpt knows this) it’s possible to do this anywhere.

Some of us go looking for fabulous cliff tops to meditate on, when all we’re going to do once we get there is close our eyes and go within.

And, as ingrid points out in her comment, “…many of us? are caught between being a part of and being apart from. we want to be heard in our society, to have an impact and yet the moment we become part of an organisation, or identify with a tribe, a cause, a country, a belief–what of our integrity?”

We go looking outside of ourselves-for ourselves. For an event to define us. But our definition-just is.

I relate to the shock of walking into the desert camo soldier at the Edmonton airport. That was the tangible revelation of my inner self and all through the trip he sat 4 rows ahead and I kept seeing and not seeing the head and shoulders.

THUS – I felt the significance of your mentioning camo, war history and England. Oscar is naked and to me feels written in the voice of a child or emerging one. It is very opening to me.

Talking with a well known Canadian Gay poet at our Sweetwater 905 festival: found it interesting how well received he was in Red Neck / Right Wing country but then realized he lives in Calgary! Therefore I became more interested that mainstream writing seems open and proud of Gays or absorbs them. I had assumed this was the same for Lesbian writers and am chagrined to note my naivety.

Oscar writes into the camouflage of gender-determined admissibles;

“do i dare go without camouflage – do I even know how” [Ingrid]

Oscar is learning how to occupy (over & over) an unbound surface that trusts the narrative’s logic, associative integrity;

“AlexAndHer speak it like this^” [Alisa]

Oscar seeks to create a coherent story full of holes that the reader can move effortlessly in & out of.

“Oscar is naked…feels written in the voice of a child…very opening to me.” [Marilyn]

An underlying question: what gets triggered when we expect an accountable narrator contrasted to a responsible narrator?

ou ou Betsy that last question….yikes

what gets triggered …………………accountable /responcible

is this even re spond able?

i feel falling thru out all these two writings

the open GAP

freeing and terrifying to exist to ACHE

guiltlessness / compelling honesty

-thanking you for this thrilling S a l o n…